The EMH

You are probably familiar with the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, but you may not be familiar with what it implies, and how it applies to the current market, regulated as it is. Read on!

What is it?

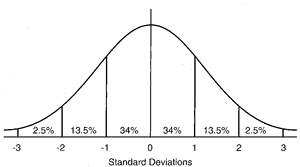

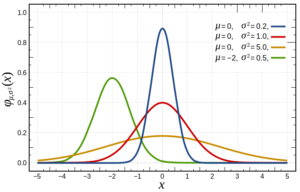

The EMH contends that security pricing reflects all known information, which is obtained quickly and enables a company’s stock to adjust rapidly. In addition, it is believed that the daily fluctuation in price is a result of a “random walk” pattern. If so, any activist strategy is thought to add no value to the process. The Bottom Line: Investors are unable to outperform the market on a consistent basis over time, and passive or “indexing” investment strategy is favored. Kudos to Dr. Eugene Fama, the “Father of the EMH”, and Dr. Burton Malkiel, an economist and author who developed the random walk notion.

The EMH has been “winning” in recent years as lots of money has flowed out of actively-traded mutual funds and into passively-managed ETF’s. Morningstar reported the following for March 2017, just as an example: “In March, investors put $31.1 billion into U.S. equity passive funds, up from $29.1 billion in February 2017. On the active side, investors pulled $18.6 billion out of U.S. equity funds during the month, as opposed to $8.9 billion in the previous month.” The latest “fund of the month” concocted by the big brokerages are out of style, and Exchange Traded Funds (ETF’s) are in. Fidelity, with a preponderance of managed funds, is “out”, and Vanguard, the forerunner of low fee indexed funds, is “in”.

There are 3 “forms” of the EMH, each with different ramifications. The “strong” form posits that stock prices currently reflect all available information, whether public or private. If the strong form were true, why is insider trading illegal, and why do investors go to jail because of insider trading? Doug DeCinces, the Baltimore Orioles’ replacement for Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson, and a subsequent California Angel, was recently convicted of insider trading, so prosecutors are still alert to it. Neither fundamental nor technical analysis are useful, which is also true for the “semi-strong” form of the EMH. Fundamental analysis may be useful under the “weak” form EMH, but Technical analysis is not useful under any EMH form. So, one can maybe reconcile the “weak” form EMH with the most famous practitioner of fundamental analysis, Warren Buffet. But, candlestick charts, head and shoulders pattern, cup and handle, support and resistance, and all of the other vocabulary associated with technical analysis? All worthless, according to any form of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Therefore it’s better just to invest in the S&P 500 Index.

What does the EMH mean for you?

If you have an IRA or a 401k, and you have some of your account invested in, let’s say, a Large Cap Growth Fund with a 5 Star Morningstar Rating, you are thumbing your nose at the Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Same with a Small Cap Value Fund, or with most funds managed by the major fund shops not named Vanguard – Fidelity, American Funds, Lord Abbett, and the like. T. Rowe Price funds do a good job of stock picking – most of the big fund families have good stock picking managers. But they are inherently not Efficient Market Hypothesis believers. All of the big mutual funds are predicated on the basis that they can use fundamental or technical analysis to outperform the market index. Instead, if you believe the EMH, you should be in an Index fund – that is, if your 401k plan administrator even offers one. (A Large Cap fund is about the same thing, but not quite). Moreover, you are paying more for lower returns – index funds tend to have much lower fees than do your standard Small Cap Value Fund.

How do you properly index-invest your portfolio and therefore abide by the EMH? You can’t do it just by investing in the SPY – the S&P 500 Index ETF, although that could be one component of your indexed portfolio. You need a domestic bond index fund, as well as international equity and bond index funds, all for asset class diversification. The older you are, the more you should be in bonds. In a recent podcast, Dr. William Sharpe, the developer of the Sharpe Ratio for measuring risk-adjusted return, and a firm EMH proponent, suggests one could adequately Index and Diversify by choosing 4 different Vanguard funds. While Dr. Sharpe did not name the 4 funds, they could be the following: Long-Term Bond Index (VBLTX), 500 Index (VFIAX), Total World Stock Index (VTWSX) and Total International Bond Index (VTABX). There are other, non-Vanguard ways to do index – more on that in a different blog post.

Free Riders

There is an issue that results from indexing, which makes total sense if you think about it: If everybody is buying index funds, who is out there watching individual companies and holding management of those companies responsible to maximize shareholder value? The S&P 500 Index rises only if the individual 500 companies perform at their best. They perform at their best only if the shareholders of those companies force them to do so. That’s why there is what is called a Free Rider problem: Index investors benefit from the diligence of the direct shareholders of the companies in the index.

IMO (In My Opinion)

I believe markets are moving toward more and more efficiency, mostly due to the increased speed at which information now flows. As a result, it is becoming increasingly difficult to invest in individual stocks and outperform consistently over a long-term. There is only one Warren Buffet, and his value-based methodology works for him because he has enough money to purchase entire companies, so he can decide how to deploy that company’s cash flow. For the rest of us, Indexing keeps us in the market, keeps us diversified, and keeps us away from single-company or single-industry “non-systemic” risk. There are ways, though, of either beating the Index, or of matching the Index with lower volatility risk, while remaining faithful to the EMH. More on that in a later blog post, as well.