Last time, in my blog titled Concentration, I wrote about how more and more of our wealth is being managed by a very few number of managers; namely, State Street, BlackRock, and Vanguard. Today, my warning is that those Big Three managers have a disproportionate amount of their assets in only a very few companies. This is a cause of concern for me as one who advises clients to invest in index funds, but I don’t see an alternative if you want to invest in the stock market, which has been the strongest asset class throughout recent history.

The Big Get Bigger

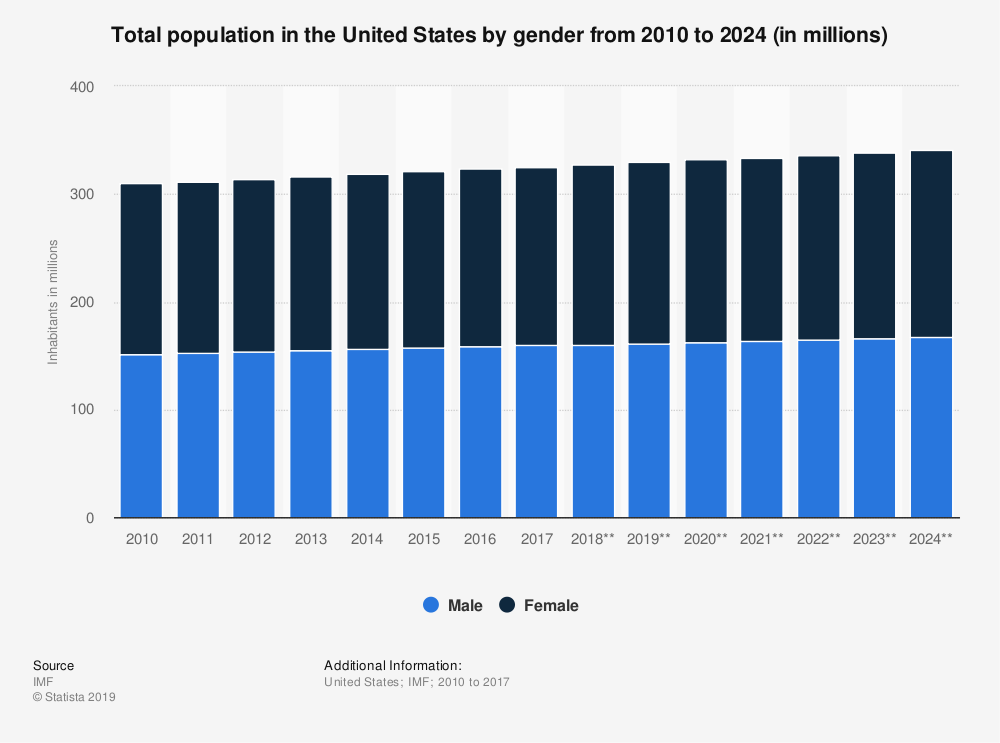

A couple of weeks ago, Alphabet, the parent of Google, became the 4th US company to achieve a Market Capitalization (Total Number of Shares Times Price Per Share) of over $1 Trillion (again, with a T). The other three are Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon. A fifth company, newly-public Saudi Aramco, is also valued at over $1 Trillion but is not a US company. These four largest companies are accounting for a larger percentage of US corporate revenue and profits, which in turn makes them a larger percentage of the various stock indexes of which they are a part, which in turn causes index ETFs such as the SPY that track these stock indexes to invest a larger percentage of their assets into these three companies. It seems like a perpetual motion machine that is headed toward greater and greater concentration of investment capital into a smaller number of companies, even though the size of the overall pie is growing.

As further proof, as of 12/31/19, according to the Fact Sheet of the SPY S&P 500 Index ETF, the top 10 holdings accounted for 22.7% of the market capitalization of the fund. So, 10 companies – the aforementioned largest 4 plus 6 others that you are also familiar with – make up 22.7% of the S&P 500 by capitalization. Does this give you pause? How about looking at the QQQ, which is the NASDAQ 100 Index ETF, which is a tech-heavy index? According to its website, the top 10 holdings in the QQQ account for 53.2% of its capitalization as of 1/17/20. Granted, this is a 100-stock index, but 53.2% for the top 10 holdings? That is very concentrated. Does this give you more pause? How about this – what if you own both the SPY and the QQQ? No surprise, but Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, and the two classes of Alphabet/Google comprise the top 6 holdings of both of these Index ETFs. You may think you are diversified, and you are more so than if you own individual stocks (if you are a small investor), but you are investing in a portfolio that is becoming more concentrated and in which the largest players are becoming even larger. This is consistent with what is happening in the larger US economy, but that doesn’t make it feel any more secure.

IMO

Diversification doesn’t just mean owning various different stocks. Diversification also means owning different asset classes, such as bonds, real estate, precious metals, and perhaps other types of assets. If you think you are more diverse by owning ETFs rather than individual stocks, you are, but that doesn’t mean you have nothing to worry about. We have an increasingly small number of asset managers managing an increasingly large percentage of our collective investment wealth and investing that wealth into a more concentrated few number of extremely large companies. Be aware of what you are getting yourself into!