President Trump on November 2, 2017, nominated Jerome Powell to succeed Janet Yellen as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank. The consensus in the media and among economic pooh-bahs is that Mr. Powell will “stay the course” – keep going with the same programs and strategies the Fed has employed over the past several years. Also, Mr. Powell is a consensus-builder, and as such will work within the Fed Board of Governors to make sure there is unity among the Governors as to what course to take. Maybe we need some consensus-building in other areas of government!

Interest Rates

The media is focused on interest rates. As most of you know, the Fed sets short-term interest rates including the discount rate. If the Fed believes the economy is getting stronger, they will raise interest rates in an effort to keep the economy from getting overheated. Conversely, the Fed will lower (short-term) interest rates to encourage economic growth if the economy stalls. Lately, the Fed has raised interest rates incrementally – up about 1% total over the past 2 years or so. It is likely the Fed will raise rates by another 0.25% when they next meet in December. It is believed Mr. Powell will not change the Fed’s program of raising rates.

Fed’s Balance Sheet

Among other programs, the Fed combatted the 2008 Financial Crisis by going on a bond-buying binge. When the Fed buys bonds in the open market, this puts money in the market for others to put to other uses, thereby (theoretically) juicing the economy. Where did the Fed get the money to buy these bonds? The short answer is: The US Treasury printed it. But, that’s not my point. My point is that the Fed still owns most of the bonds that they bought as a result of the Financial Crisis. Bonds that the Fed buy go on the Fed’s own Balance Sheet as Assets.

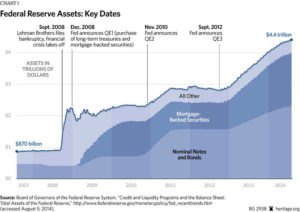

The following is a chart by the Heritage Foundation that shows how much the Fed’s Assets have increased over time. The chart shows the period from 2008 to 2014; the Fed’s Assets have remained about the same since 2014:

The following is a link to the Fed’s website that shows the current Fed Balance Sheet. The chart there is interactive so I couldn’t copy and paste it, but at least I can link to it and you can see it for yourself: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

$4.4 Trillion

You are reading that correctly: The Fed owns about $4.4 Trillion of assets, maybe $4.5 Trillion now – mostly mortgage and other notes and bonds. That’s with a Capital T. That’s a ton of money, and it has remained that high for the past 3 years. Prior to the Financial Crisis, The Fed’s assets were under $1 Trillion. In October 2017, the Fed commenced an “unwinding” program whereby they will reduce their holdings by $10 Billion per month and increasing gradually over time. So, the Fed is now reducing its balance sheet.

Enough?

My questions: Is $10 Billion per month enough? Does the Fed really need to keep $4.4 Trillion of assets? Shouldn’t the Fed “unwind” its Balance Sheet much quicker? The Fed’s twin objectives (per Congress) are to minimize inflation and maximize employment. Currently, inflation is low (under 2% annually) and unemployment is also low (well under 5%, at least how the Department of Labor measures it). One could argue that the Fed’s past policies succeeded – that the reason we have low inflation, low unemployment, and a relatively healthy economy now is precisely because the Fed went bond-buying buying spree after 2008.

IMO

The media and others have increased their focus on the Fed in recent years, especially since the 2008 Financial Crisis, because for many years Congress couldn’t get its act together and pass an actual budget. Recall all of those times the US Government was funded based on “continuing resolutions”. Fiscal Policy (i.e., congressional spending) was off the table due to congressional dysfunction, so Monetary Policy (promulgated by the Fed) took center stage. It was never solely the Fed’s responsibility to “save” the economy during and after the Financial Crisis, yet the media portrayed it as such. Currently, the economy is much stronger, yet the Fed’s Balance Sheet remains at crisis levels. $10 Billion of “unwind” per month doesn’t make much of a dent in $4.4 Trillion. At $10 Billion per month, that’s 10 months for $100 Billion of “unwind”, and 100 months (or 8.3 years) for $1 Trillion of “unwind”. I think the pace of the unwinding should be much faster, and I think the focus should be on this instead of on the short-term interest rates. The US Economy is currently strong enough to handle the Fed unwinding its balance sheet much faster. The Fed should use this opportunity to “re-arm” in a sense, so as to put itself in a better position to deal with the next financial crisis, if and when it arises. Perhaps the Fed is, in fact, planning to do so. Perhaps Mr. Powell will use his consensus-building skills to point the Fed in the direction of more rapid unwinding.